Three dynasty and 1 kingdom

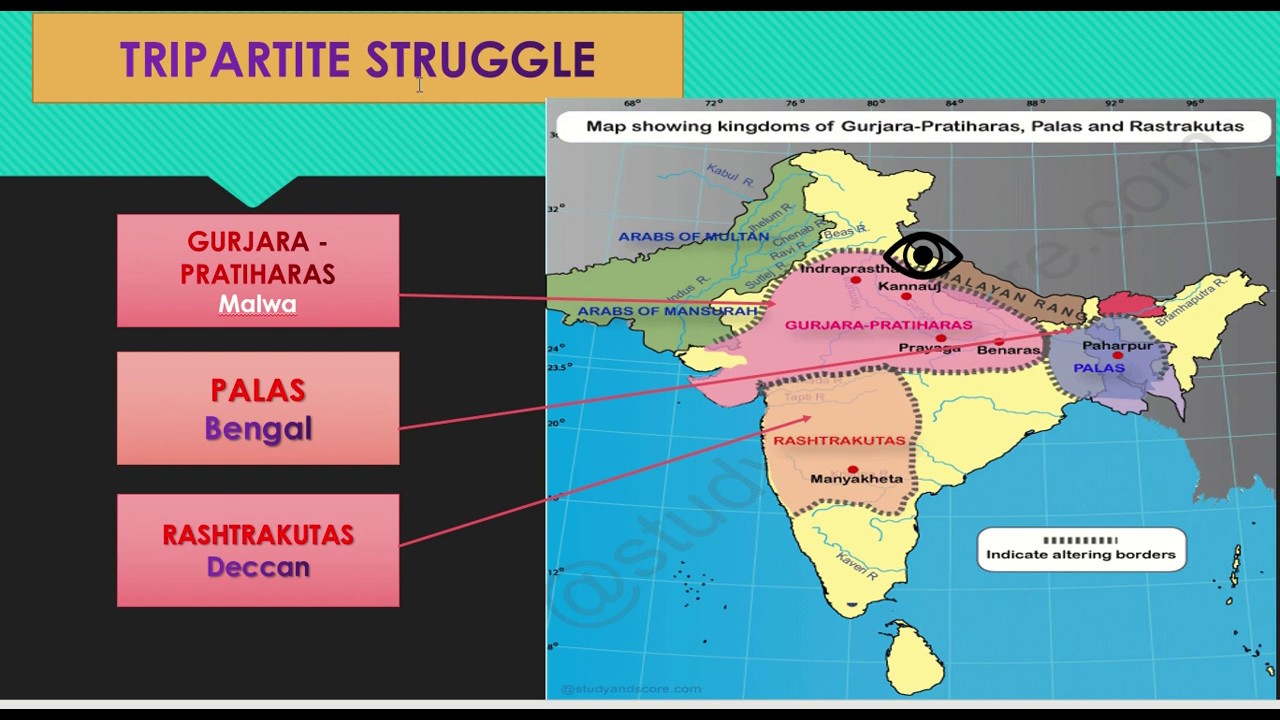

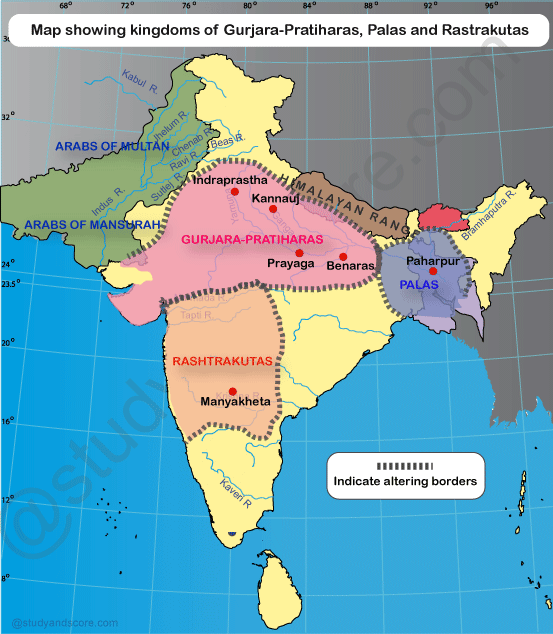

The Tripartite Struggle, also known as the Kannauj Triangle Wars, took place in the 8th and 9th centuries, between the three great Indian dynasties, the Palas, the Pratiharas, and the Rashtrakutas, for control over the Kannauj area of northern India. The Palas ruled India's eastern regions (Bengal region), while the Pratiharas oversaw India's western regions (Avanti-Jalaor region) and the Deccan area of India was dominated by the Rastrakutas. This war lasted for two centuries and was finally won by the Rajput Pratihara emperor Nagabhata II, who established the city as the capital of the Pratihara state, which ruled for nearly three centuries. This article will explain to you the Tripartite struggle which will be helpful in History preparation for the UPSC Civil service exam1.Why did The Tripartite struggle start?

2. Kingdoms in Tripartite struggle Phase 1

Rashtrakuta (IAST: rāṣṭrakūṭa) (r. 753-982 CE) was a royal Indian dynasty ruling large parts of the Indian subcontinent between the sixth and 10th centuries. The earliest known Rashtrakuta inscription is a 7th-century copper plate grant detailing their rule from manapur a city in Central or West India. Other ruling Rashtrakuta clans from the same period mentioned in inscriptions were the kings of Achalapur and the rulers of Kannauj. Several controversies exist regarding the origin of these early Rashtrakutas, their native homeland and their language.

The Elichpur clan was a feudatory of the Badami Chalukyas, and during the rule of Dantidurga, it overthrew Chalukya Kirtivarman II and went on to build an empire with the Gulbarga region in modern Karnataka as its base. This clan came to be known as the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta, rising to power in South India in 753 AD. At the same time, the Pala dynasty of Bengal and the Prathihara dynasty of Malwa were gaining force in eastern and northwestern India respectively. An Arabic text, Silsilat al-Tawarikh (851), called the Rashtrakutas one of the four principal empires of the world.

Between the eighth and the 10th centuries, this period saw a tripartite struggle for the resources of the rich Gangetic plains, each of these three empires annexing the seat of power at Kannauj for short periods. At their peak, the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta ruled a vast empire stretching from the Ganges River and Yamuna River doab in the north to Kanyakumari in the south, a fruitful time of political expansion, architectural achievements and famous literary contributions. The early kings of this dynasty were influenced by Hinduism and the later kings by Jainism.

Jain mathematicians and scholars contributed important works in Kannada and Sanskrit during their rule. Amoghavarsha I, the most famous king of this dynasty wrote Kavirajamarga, a landmark literary work in the Kannada language. Architecture reached a milestone in the Dravidian style, the finest example of which is seen in the Kailasanatha Temple at Ellora in modern Maharashtra. Other important contributions are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in modern Karnataka, both of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The ascent of Dhruva Dharavarsha's third son, Govinda III, to the throne, heralded an era of success like never before. There is uncertainty about the location of the early capital of the Rashtrakutas at this time. During his rule, there was a three-way conflict between the Rashtrakutas, the Palas and the Pratiharas for control over the Gangetic plains. Describing his victories over the Pratihara Emperor Nagabhatta II and the Pala Emperor Dharmapala, the Sanjan inscription states the horses of Govinda III drank from the icy waters of the Himalayan streams and his war elephants tasted the sacred waters of the Ganges. His military exploits have been compared to those of Alexander the Great and Arjuna of Mahabharata. Having conquered Kannauj, he travelled south, took firm hold over Gujarat, Kosala (Kaushal), and Gangavadi, humbled the Pallavas of Kanchi, installed a ruler of his choice in Vengi and received two statues as an act of submission from the king of Ceylon (one statue of the king and another of his minister). The Cholas, the Pandyas and the Kongu Cheras of Karur all paid him tribute. As one historian puts it, the drums of the Deccan were heard from the Himalayan caves to the shores of the Malabar Coast. The Rashtrakutas empire now spread over the areas from Cape Comorin to Kannauj and from Banaras to Bharuch.

The successor of Govinda III, Amoghavarsha I made Manaykheta his capital and ruled a large empire. Manyakheta remained the Rashtrakutas' regal capital until the end of the empire. He came to the throne in 814 but it was not until 821 that he suppressed revolts from his feudatories and ministers. Amoghavarsha I made peace with the Western Ganga Dynasty by giving them his two daughters in marriage, and then defeated the invading Eastern Chalukyas at Vingavalli and assumed the title Viranarayana. His rule was not as militant as that of Govinda III as he preferred to maintain friendly relations with his neighbours, the Ganges, the Eastern Chalukyas and the Pallavas with whom he also cultivated marital ties. His era was an enriching one for the arts, literature and religion. Widely seen as the most famous of the Rashtrakuta Emperors, Amoghavarsha I was an accomplished scholar in Kannada and Sanskrit. His Kavirajamarga is considered an important landmark in Kannada poetics and Prashnottara -in Sanskrit is a writing of high merit and was later translated into the Tibetan language. Because of his religious temperament, his interest in the arts and literature and his peace-loving nature, he has been compared to the emperor Ashoka and called "Ashoka of the South".

During the rule of Krishna II, the empire faced a revolt from the Eastern Chalukyas and its size decreased to the area including most of the Western Deccan and Gujarat. Krishna II ended the independent status of the Gujarat branch and brought it under direct control from Manyakheta. Indra III recovered the dynasty's fortunes in central India by defeating the Paramara and then invaded the Doab region of the Ganges and Jamuna rivers. He also defeated the dynasty's traditional enemies, the Pratiharas and the Palas, while maintaining his influence over Vengi. The effect of his victories in Kannauj lasted several years according to the 930 copper plate inscription of Emperor Govinda IV. After a succession of weak kings during whose reigns the empire lost control of territories in the north and east, Krishna III the last great ruler consolidated the empire so that it stretched from the Narmada River to the Kaveri River and included the northern Tamil country (Tondaimandalam) while levying tribute on the king of Ceylon.

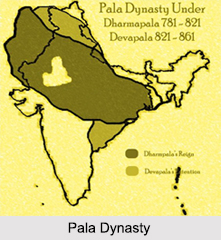

The Pala Empire (r. 750-1161 CE) was an imperial power during the post-classical period in the Indian subcontinent, which originated in the region of Bengal. It is named after its ruling dynasty, whose rulers bore names ending with the suffix Pala ("protector" in Prakrit). The empire was founded with the election of Gopala as the emperor of Gauda the in late eighth century AD. The Pala stronghold was located in Bengal and eastern Bihar, which included the major cities of Gauda, Vikrampura, Pataliputra, Monghyr, Somapura, Ramvati (Varendra), Tamralipta and Jaggadala. The Palas were astute diplomats and military conquerors. Their army was noted for its vast war elephant corps. Their navy performed both mercantile and defensive roles in the Bay of Bengal. At its zenith under emperors Dharmapala and Devapala in the early ninth century, the Pala empire extended its dominance into the northern Indian region, with its territory stretching across the Gangetic plain to include some parts of western, southern and northeastern India, Nepal and Bangladesh. Dharmapala also exerted a strong cultural influence through Buddhist scholar Atis Dipankar in Tibet, as well as in Southeast Asia. Pala's control of North India was ultimately ephemeral, as they struggled with the Gurjara-Pratiharas and the Rashtrakutas for the control of Kannauj and were defeated. After a short-lived decline, Emperor Mahipala I defended imperial bastions in Bengal and Bihar against South Indian Chola invasions. Emperor Ramapala

was the last strong Pala ruler, who gained control of Kamarupa and Kalinga. The empire was considerably weakened with many areas engulfed and their heavy dependence on Samanthas being exposed through the 11th-century rebellion. It finally led to the rise of resurgent Hindu Senas as a sovereign power in the 12th century and the final expulsion of the Palas from Bengal by their hands marking the end of the last major Buddhist imperial power in the subcontinent. The Pala period is considered one of the golden eras of Bengali history. The Palas brought stability and prosperity to Bengal after centuries of civil war between warring divisions. They advanced the achievements of previous Bengali civilisations and created outstanding works of art and architecture. The Charyapada in Proto-Bengali language was written by Buddhist Mahasiddhas of tantric tradition, which laid the basis of several eastern Indian languages during their rule. Palas built grand temples and monasteries, including the Somapura Mahavihara and Odantapuri, and patronised the great universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila. The empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first arrived in Bengal during this period as a result of flourishing mercantile and intellectual contacts with the Middle East. The Pala legacy is still reflected in Tibetan Buddhism. Gopala's empire was greatly expanded by his son Dharmapala and his grandson Devapala. Dharmapala was initially defeated by the Pratihara ruler Vatsaraja. Later, the Rashtrakuta king Dhruva defeated both Dharmapala and Vatsaraja. After Dhruva left for the Deccan region, Dharmapala built a mighty empire in northern India. He defeated the Indrayudha of Kannauj and installed his own nominee Chakrayudha on the throne of Kannauj. Several other smaller states in North India also acknowledged his suzerainty. Soon, his expansion was checked by Vatsaraja's son Nagabhata II, who conquered Kannauj and drove away Chakrayudha. Nagabhata II then advanced up to Munger and defeated Dharmapala in a pitched battle. Dharmapala was forced to surrender and seek an alliance with the Rashtrakuta emperor Govinda III, who then intervened by invading northern India and defeating Nagabhata II. The Rashtrakuta records show that both Chakrayudha and Dharmapala recognised the Rashtrakuta suzerainty. In practice, Dharmapala gained control over North India after Govinda III left for the Deccan. He adopted the title Paramesvara Paramabhattaraka Maharajadhiraja.

Dharmapala was succeeded by his son Devapala, who is regarded as the most powerful Pala Emperor. His expeditions resulted in the invasion of Pragjyotisha (present-day Assam) where the king submitted without giving a fight and the Utkala (present-day Northern Odisha) whose king fled from his capital city. The inscriptions of his successors also claim several other territorial conquests by him, but these are possibly exaggerated (see the Geography section below).

His oldest son, Rajyapala predeceased him, and so Mahendrapala, his next older son succeeded him. He possibly maintained his father's vast territories and carried out further campaigns against the Utkalas and the Hunas. He passed his empire intact to his younger brother Shurapala I, who held sway over a considerably large territory encompassing Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, proven by his Mirzapur copperplate. What happened during Gopala II's rule, the son of Surapala I, is still unknown. After Gopala II, Dharmapala's line came to an end for reasons which are not known yet. Dharmapala's descendants, if any, were passed over as Dharmapala's younger brother, Vakapala's lineage assumed the throne.

Rapala was the final strong Pala Emperor, although his son Kumarapala managed to keep most of his territories. After his death, a rebellion broke out in Kamarupa during his son Kumarapala's reign. The rebellion was crushed by Vaidyadeva, minister of Kumarapala. Vaidyadeva also won a naval war in southern Bengal for his liege. but after Kumarapala's death, Vaidyadeva practically created a separate kingdom. Kumarapala's son, Gopala IV ascended the throne as a child, and according to the Rajibpur copperplate inscription, his uncle Madanpala acted as his regent. Gopala IV either died in battle or was murdered by Madanapala. During Madanapala's rule, the Burmans in east Bengal declared independence, and the Eastern Gangas renewed the conflict in Orissa. Madanapala captured Munger from the Gahadavalas but was defeated by Vijayasena, who gained control of southern and eastern Bengal. Two rulers, named Govindapala and Palapala ruled over the Gaya district from around 1162 CE to 1200 CE, but there is no concrete evidence of their relationship to the imperial Palas. The Pala dynasty was replaced by the Sena dynasty. The descendants of the Palas, who claimed the status of Kshatriya, "almost imperceptibly merged" with the Kayastha caste

Gurjara-Pratiharas

The Gurjara-Pratihara was a dynasty that ruled much of Northern India from the mid-8th to the 11th century. They ruled first at Ujjain and later at Kannauj.

The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River. Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid Taeminamin in the Caliphate campaigns in India. Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India.

He was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly before being succeeded by his son, Mihira Bhoja. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty reached its peak of prosperity and power. By the time of Mahendrapala, the extent of its territory rivalled that of the Gupta Empire stretching from the border of Sindh in the west to Bengal in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to areas past the Narmada in the south. The expansion triggered a tripartite power struggle with the Rashtrakuta and Pala empires for control of the Indian subcontinent. During this period, Imperial Pratihara took the title of Maharajadhiraja of Āryāvarta (Great King of Kings of Aryan Lands).

2. Kingdoms in Tripartite struggle Phase 1

RashtrakutaIn 972 A.D., during the rule of Bottega Amoghavarsha, the Paramara King Siyaka Harsha attacked the empire and plundered Manyakheta, the capital of the Rashtrakutas. This seriously undermined the reputation of the Rastrakuta Empire and consequently led to its downfall. The final decline was sudden as the Tailapa II, a feudatory of the Rashtrakuta ruling from Tardavadi province in modern Bijapur District, declared himself independent by taking advantage of this defeat. Indra IV, the last emperor, committed Sallekhana (fasting unto death practised by Jain monks) at Shravanabelagola. With the fall of the Rashtrakutas, their feudatories and related clans in the Deccan and northern India declared independence.

The Western Chalukyas annexed Manyakheta, made it their capital until 1015 and built an impressive empire in the Rashtrakuta heartland during the 11th century. The focus of dominance shifted to the Krishna River – Godavari River doab called Vengi. The former feudatories of the Rashtrakutas in western Deccan were brought under the control of the Chalukyas, and the hitherto-suppressed Cholas of Tanjore became their arch-enemies in the south.

In conclusion, the rise of the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta greatly impacted India, even in India's north. Sulaiman (851), Al-massage (944) and Ibn Khurdadba (912) wrote that their empire was the largest in contemporary India and Sulaiman further called it one of the four great contemporary empires of the world. According to the travelogues of the Arabs Al Masudi and Ibn Khordidbih of the 10th century, "most of the kings of Hindustan turned their faces towards the Rashtrakuta king while they were praying, and they prostrated themselves before his ambassadors. The Rashtrakuta king was known as the "King of kings" (Rajadhiraja) who possessed the mightiest of armies and whose domains extended from Konkan to Sind." Some historians have called these times an "Age of Imperial Kannauj". Since the Rashtrakutas successfully captured Kannauj, levied tribute on its rulers and presented themselves as masters of North India, the era could also be called the "Age of Imperial Karnataka".During their political expansion into central and northern India in the 8th to the 10th centuries, the Rashtrakutas or their relatives created several kingdoms that either ruled during the reign of the parent empire or continued to rule for centuries after its fall or came to power much later. Well known among these were the Rashtrakutas of Gujarat(757-888), the Rattas of Saundatti (875–1230) in modern Karnataka, the Gahadavalas of Kannauj (1068–1223), the Rashtrakutas of Rajasthan (known as Rajputana) and ruling from Hastikundi or Hathundi (893–996), Dahal, Rathores of Mandore (near jodhpur), the Rathores of Dhanop, Rashtraudha dynasty of Mayuragiri in modern Maharashtra and Rashtrakutas of Kannauj. Rajadhiraja Chola's conquest of the island of Ceylon in the early 11th century CE led to the four kings' fall. According to historian K. Pillay, one of them, King Madavarajah of the Jaffna Kingdom, was a usurper from the Rashtrakuta Dynasty.

Pala Empire

|

| Coins of Pala Empire Under Mahipala |

Naryanapala's son Rajyapala ruled for at least 32 years and constructed several public utilities and lofty temples. Earlier it was thought that his son Gopala III lost Bengal after a few years of rule, and then ruled only Bihar. However, it has been debunked by his Bhagalpur inscription, in which he granted a Brahmin two villages in Pundrabardhanabhukti in Northern Bengal, signalling his control over it. His son and the next king, Vigrahapala II, had to bear the invasions from the Chandelas and the Kalachuris. During his reign, the Pala empire disintegrated into smaller kingdoms like Gauda, Radha, Anga and Vanga. Kantideva of Harikela (eastern and southern Bengal) also assumed the title Maharajadhiraja, and established a separate kingdom, later ruled by the Chandra dynasty. The Gauda state (West and North Bengal) was ruled by the Kamboja Pala dynasty. The rulers of this dynasty also bore names ending in the suffix -pala (e.g. Rajyapala, Narayanapala and Nayapala). However, their origin is uncertain, and the most plausible view is that they originated from a Pala official who usurped a major part of the Pala kingdom along with its capital. Mahipala I recovered northern and eastern Bengal within three years of ascending the throne in 978 CE. he also recovered his capital, Gauda, which had been lost to the Kambojas.

He also recovered the northern part of the present-day Burdwan division. During his reign, Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire frequently invaded Bengal from 1021 to 1023 CE to get Ganges water and in the process, succeeded to humble the rulers, acquiring considerable booty. The rulers of Bengal who were defeated by Rajendra Chola were Dharmapal, Ranasur and Govindachandra, who might have been feudatories under Mahipala I of the Pala Dynasty. Rajendra Chola I also defeated Mahipala, and obtained from the Pala king "elephants of rare strength, women and treasure". Mahipala also gained control of the north and south Bihar, probably aided by the invasions of Mahmud of Ghazni, which exhausted the strength of other rulers of North India. He may have also conquered Varanasi

and the surrounding area, as his brothers Sthirapala and Vasantapala undertook construction and repairs of several sacred structures at Varanasi. Later, the Kalachuri king Gangeyadeva annexed Varanasi after defeating the ruler of Anga, which was probably Mahipala's son Nayapala. After gaining control of Varendra, Ramapala tried to revive the Pala empire with some success. He ruled from a new capital at Ramavati, which remained the Pala capital until the dynasty's end. He reduced taxation, promoted cultivation and constructed public utilities. He brought Kamarupa and Rar under his control and forced the Varman king of east Bengal to accept his suzerainty. He also struggled with the Ganga king for control of present-day Orissa; the Ganga managed to annex the region only after his death. Rapala maintained friendly relations with the Chola king Kulottunga to secure support against the common enemies: the Ganas and the Chalukyas. He kept the Senas in check but lost Mithila to a Karnataka chief named Nanyuadeva. He also held back the aggressive design of the Gahadavala ruler Govindacharndra through a matrimonial alliance, by marrying off his cousin Kumaradevi to the king. Ramapala was the final strong Pala Emperor, although his son Kumarapala managed to keep most of his territories. After his death, a rebellion broke out in Kamarupa during his son Kumarapala's reign. The rebellion was crushed by Vaidyadeva, minister of Kumarapala. Vaidyadeva also won a naval war in southern Bengal for his liege. but after Kumarapala's death, Vaidyadeva practically created a separate kingdom. Kumarapala's son, Gopala IV ascended the throne as a child, and according to the Rajibpur copperplate inscription, his uncle Madanpala acted as his regent. Gopala IV either died in battle or was murdered by Madanapala. During Madanapala's rule, the Varmans in east Bengal declared independence, and the Eastern Gangas renewed the conflict in Orissa. Madanapala captured Munger from the Gahadavalas but was defeated by Vijayasena, who gained control of southern and eastern Bengal. Two rulers, named Govindapala and Palapala ruled over the Gaya district from around 1162 CE to 1200 CE, but there is no concrete evidence of their relationship to the imperial Palas. The Pala dynasty was replaced by the Sena dynasty. The descendants of the Palas, who claimed the status of Kshatriya, "almost imperceptibly merged" with the Kayastha caste.

Gurjara-PratiharasAfter bringing much of Rajasthan

under his control, Vatsaraja embarked to become "master of all the land lying between the two seas." Contemporary Jijasena's Harivamsha Purana describes him as the "master of the western quarter"

According to the Radhanpur Plate and Prithviraj Vijaya, Vatsaraja led an expedition against the Palas under Dharmapala of Bengal As such, the Palas came into conflict from time to time with the Imperial Pratiharas. According to the above inscription, Dharmapala was deprived of his two white Royal Umbrellas, and fled, followed by the Pratihara forces under general Durlabharaja Chauhan of Shakambhari. The Prithviraj Vijaya mentions Durlabhraj I as having "washed his sword at the confluence of the river Ganga and the ocean, and savouring the land of the Goudas", The Baroda Inscription (AD 812) states Nagabhata defeated the Dharmapala. Through vigorous campaigning, Vatsraj had extended his dominions to include a large part of northern India, from the Thar Desert in the west up to the frontiers of Bengal in the east.

The metropolis of Kannauj had suffered a power vacuum following the death of Harsha without an heir, which resulted in the disintegration of the Empire of Harsha. This space was eventually filled by Yashovarman around a century later but his position was dependent upon an alliance with Lalitaditya Muktapida. When Muktapida undermined Yashovarman, a tri-partite struggle for control of the city developed, involving the Pratiharas, whose territory was at that time to the west and north, the Palas of Bengal in the east and the Rashtrakutas, whose base lay at the south in the Deccan. Vatsaraja successfully challenged and defeated the Pala ruler Dharmapala and Dantidurga, the Rashtrakuta king, for control of Kannauj.

Around 786, the Rashtrakuta ruler Dhruva (c. 780–793) crossed the Narmada River into Malwa, and from there tried to capture Kannauj. Vatsraja was defeated by the Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty around 800. Vatsaraja was succeeded by Nagabhata II (805–833), who was initially defeated by the Rashtrakuta ruler Govinda III (793–814), but later recovered Malwa from the Rashtrakutas, conquered Kannauj and the Indo-Gangetic Plain as far as Bihar from the Palas, and again checked the Muslims in the west. He rebuilt the great Shiva temple at Somnath in Gujarat, which had been demolished in an Arab raid from Sindh. Kannauj became the centre of the Gurjara-Pratihara state, which covered much of northern India during the peak of their power, c. 836–910. Gurjara-Pratihara is known for its sculptures, carved panels and open pavilion-style temples. The greatest development of their style of temple building was at Khajuraho, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The power of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty was weakened by dynastic strife. It was further diminished as a result of a great raid led by the Rashtrakuta ruler Indra III who, in about 916, sacked Kannauj. Under a succession of rather obscure rulers, the dynasty never regained its former influence. Their feudatories became more and more powerful, one by one throwing off their allegiance until, by the end of the tenth century, the dynasty controlled little more than the Gangetic Doab. Their last important king, Rajyapala, was driven from Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1018.

Chola Dynasty

There is very little written evidence

ce for the Cholas before the 7th century CE. The main sources of information about the early Cholas are ancient Tamil literature of the Sangam Period., oral traditions, religious texts, and temple and copperplate inscriptions. Later medieval Cholas also claimed a long and ancient lineage. The Cholas are mentioned in Ashokan Edicts (inscribed 273 BCE–232 BCE) as one of the Mauryan Empire's neighbours to the South, who, though not subject to Ashoka, was on friendly terms with him. There are also brief references to the Chola country and its towns, ports and commerce in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (Periplus Maris Erythraei), and in the slightly later work of the geographer Ptolemy. Mahavamsa, a Buddhist text written down during the 5th century CE, recounts several conflicts between the inhabitants of Sri Lanka and Cholas in the 1st century BCE.

A commonly held view is that Chola is, like Chera and Pandya, the name of the ruling family or clan of immemorial antiquity. The annotator Parimelazhagar said: "The charity of people with ancient lineage (such as the Cholas, the Pandyas and the Cheras) are forever generous despite their reduced means". Other names in common use for the Cholas are Choda., Killi (கிள்ளி), Valavan (வளவன்), Sembiyan (செம்பியன்) and Cenni. Killi perhaps comes from the Tamil kil (கிள்) meaning dig or cleave and conveys the idea of a digger or a worker of the land. This word often forms an integral part of early Chola names like Nedunkilli, Nalankilli and so on, but almost drops out of use in later times. Valavan is most probably connected with "valam" (வளம்) – fertility and means owner or ruler of a fertile countrySembilanan is generally taken to mean a descendant of Shibi – a legendary hero whose self-sacrifice in saving a dove from the pursuit of a falcon figures among the early Chola legends and forms the subject was a matter of the Sibi Jataka among the Jataka stories of Buddhism. Ithe n Tamil lexicon Chola means Soazhi or Saei denoting a newly formed kingdom, along the lines of Pandya or the old country. Cenni in Tamil means Head. During the reign of Rajaraja Chola I and his successors

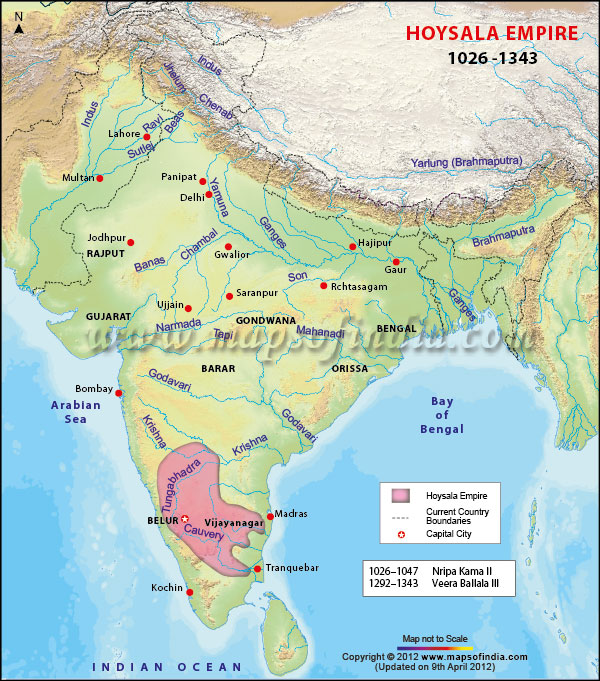

The Later Chola dynasty was led by capable rulers such as Kulothunga Chola I, his son Vikrama Chola, and their successors like Rajaraja Chola II, Rajadhiraja Chola II, and Kulothunga Chola III, who conquered Kalinga, Ilam, and Kataha. However, the rule of the later Cholas between 1218, starting with Rajaraja Chola II, to the last emperor Rajendra Chola III was not as strong as those of the

emperors between 850 and 1215. Around 1118, they lost control of Vengi to the Western Chalukya and Gangavadi (southern Mysore districts) to the Hoysala Empire. However, these were only temporary setbacks, because immediately following the accession of king Vikrama Chola, the son and successor of Kulothunga Chola I, the Cholas lost no time in recovering the province of Vengi by defeating Chalukya Someshvara III and also recovering Gangavadi from the Hoysalas. The Chola Empire, though not as strong as between 850 and 1150, was still largely territorially intact under Rajaraja Chola II (1146–1175) a fact attested by the construction and completion of the third grand Chola architectural marvel, the chariot-shaped Airavatesvara Temple at Dharasuram on the outskirts of modern Kumbakonam. Chola administration and territorial integrity until the rule of Kulothunga Chola III were stable and very prosperous up to 1215, but during his rule itself, the decline of the Chola power started following his defeat by Maravarman Sundara Pandiyan II in 1215–16. Subsequently, the Cholas also lost control of the island of Lanka and were driven out by the revival of Sinhala power. The Cholas, under Rajaraja Chola III and later, his successor Rajendra Chola III were quite weak and therefore, experienced continuous trouble. One feudatory, the Kadava chieftain Kopperunchinga I, even held Rajaraja Chola III hostage for some time. At the close of the 12th century, the growing influence of the Hoysalas replaced the declining Chalukyas as the main player in the Kannada country, but they too faced constant trouble from the Saunass and the Kalachuris, who were occupying the Chalukya capital becathe those empires were their new rivals. So naturally, the Hoysalas found it convenient to have friendly relations with the Cholas from the time of Kulothunga Chola III, who had defeated Hoysala Veera Ballala II, who had subsequent marital relations with the Chola monarch. This continued during the time of Rajaraja Chola III the son and successor of Kulothunga Chola III

The Hoysalas played a divisive role in the politics of the Tamil country during this period. They thoroughly exploited the lack of unity among the Tamil kingdoms and alternately supported one Tamil kingdom against the other thereby preventing both the Cholas and Pandyas from rising to their full potential. During the period of Rajaraja III, the Hoysalas sided with the Cholas and defeated the Kadava chieftain Kopperunjinga and the Pandyas and established a presence in the Tamil country. Rajendra

Chola III who succeeded Rajaraja III was a much better ruler who took bold steps to revive the Chola fortunes. He led successful expeditions to the north as attested by his epigraphs found as far as Cuddappah. He also defeated two Pandya princes one of whom was Maravarman Sundara Pandya II and briefly made the Pandyas submit to the Chola overlordship. The Hoysalas, under Vira Someswara, were quick to intervene and this time they sided with the Pandyas and repulsed the Cholas to counter the latter's revival. The Pandyas in the south had risen to the rank of a great power who ultimately banished the Hoysalas from Malanadu or Kannada country, who were allies of the Cholas from Tamil country and the demise of the Cholas themselves ultimately was caused by the Pandyas in 1279. The Pandyas first steadily gained control of the Tamil country as well as territories in Sri Lanka, southern Chera country, and Telugu country under Maravarman Sundara Pandiyan II and his able successor Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan before inflicting several defeats on the joint forces of the Cholas under Rajaraja Chola III, and the Hoysalas under Someshwara, his son Ramanatha The Pandyans gradually became major players in the Tamil country from 1215 and intelligently consolidated their position in Madurai-Rameswaram-Ilam-southern Chera country and Kanyakumari belt, and had been steadily increasing their territories in the Kaveri belt between Dindigul-Tiruchy-Karur-Satyamangalam as well as in the Kaveri Delta i.e., Thanjavur-Mayuram-Chidambaram-Vriddhachalam-Kanchi, finally marching all the way up to Arcot—Tirumalai-Nellore-Visayawadai-Vengi-Kalingam belt by 1250.

The Pandyas steadily routed both the Hoysalas and the Cholas. They also dispossessed the Hoysalas, by defeating them under Jatavarman Sundara Pandiyan at Kannanur Kuppam. At the close of Rajendra's reign, the Pandyan empire was at the height of prosperity and had taken the place of the Chola empire in the eyes of foreign observers. The last recorded date of Rajendra III is 1279. There is no evidence that Rajendra was followed immediately by another Chola prince. The Hoysalas were routed from Kannanur Kuppam around 1279 by Kulasekhara Pandiyan and in the same war the last Chola emperor Rajendra III was routed and the Chola empire ceased to exist thereafter. Thus the Chola empire was completely overshadowed by the Pandyan empire and sank into obscurity by the end of the 13th century and until the period of the Vijayanagara empire. In the early 16th century, Virasekhara Chola, king of Tanjore rose out of obscurity and plundered the dominions of the then Pandya prince in the south. The Pandya who was under the protection of the Vijayanagara appealed to the emperor and the KrisnaRaya accordingly directed his agent (Karyakartta) Nagama Nayaka who was stationed in the south to put down the Chola. Nagama Nayaka then defeated the Chola but to everyone's surprise, the once loyal officer of Krishnadeva Raya defied the emperor for some reason and decided to keep Madurai for himself. Krishnadeva Raya is then said to have dispatched Nagama's son, Viswanatha who defeated his father and restored Madurai to Vijayanagara. The fate of Virasekhara Chola, the last of the line of Cholas is not known. It is speculated that he either fell in battle or was put to death along with his heirs during his encounter with Vijayanagara. However, the Chola dynasty seemed to have survived elsewhere outside of India. According to Cebuano oral legends, a rebel branch of the Chola dynasty continued to survive in the Philippines up until the 16th Century, a local Malayo-Tamil Indianized kingdom called the Rajahnate of Cebu which settled in the island of Cebu which was founded by Rajamuda Sri Lumay who was half Tamil, half Malay. He was born in the previous Chola-occupied Srivijaya. He was sent by the Maharajah to establish a base for expeditionary forces, but he rebelled and established his own independent rajahnate. The Indianized kingdom flourished until its eventual conquest by Conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, who sailed to the Philippines from Mexico with his Spanish and Latino soldiers.

Which and how did kingdoms emerge due to this?

Chandella Dynasty

Chola Dynasty

Chauhan dynasty

Vengi

Tomaras

Common Questions about tripartite?

Question A.1:

Name the kingdoms both foreign and Indian which emerged during the period 700 − 1200 AD.

ANSWER:

The early mediaeval period AD 700–1200 saw the emergence of a number of powerful regional kingdoms in north India, the Deccan and south India. These kingdoms have been listed below.

The Palas

The Gurjara-Pratiharas

The Rashtrakutas

The Cholas

The Turks

Question A.2:

What did the Arab travellers say about the Rashtrakuta kingdom?

ANSWER:

Sulaiman, an Arab traveller, visited Amoghavarsa's court in AD 851. He wrote that the Rashtrakuta kingdom had reached its zenith under Amoghvarsa's rule. He also wrote that the Rashtrakuta dynasty was one of the four great empires of the world.

Question A.3:

What do you understand by the tripartite struggle?

ANSWER:

The constant rivalry between the Palas, the Gurjara-Pratiharas and the Rashtrakutas has been termed the Tripartite Struggle or the struggle between three major powers. One of the major causes of this continuous struggle was the desire to possess the city of Kannauj, which was then a symbol of sovereignty. Another cause was the control of the fertile regions of the Ganges valley.

Question A.4:

Where did Turkish invasions take place?

ANSWER:

The prominent Turkish ruler Mahmud Ghazni invaded Punjab and annexed eastern provinces. He later looted the cities of Thaneswar, Mathura, Kannauj and Somnath.

Question A.5:

Mention two famous kings of Chola kingdom.

ANSWER:

The Chola kingdom reached great heights under the reign of Rajaraja I and his son Rajendra I.

Question B.1:

Highlight the main reasons behind the success of Turks in India.

ANSWER:

Some of the reasons behind the success of the Turks in India are as follows:

After the fall of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, no single dominant dynasty came into power. Instead, several small independent powers such as the Gahadavalas of Kannauj, the Parmaras of Malwa and the Chauhans of Ajmer emerged as powers in different parts of the country. These powers remained busy overpowering each other or extending their areas of authority. This left the country with with powerful authority to check any invasion.

A form of feudal military arrangement existed in the Hindu states. In this system, feudal lords had small army regiments under their control. During the time of milithe tary expedition, the feudal lords extended their aid to the king. This system reduced the loyalty to the king. This resulted in lack of unity and coordination in the army.

Superior military technology and well-crafted art of warfare of the Turks were also some reasons for the theircess of the Turks.

Question B.2:

Village assemblies were an important part of Chola administration. How?

ANSWER:

Village assemblies were an important part of the Chola administration (society and polity). A self-sufficient and autonomous village was established with the help of these assemblies. The assemblies worked from the grasgrassrootsel, with participation of all villagers. At the top of the system, there were several officers and committees overlooking the work of autonomous units. According to the Uttaramerur inscriptions, therthree types of assemblies playedrominent role in the local administration. These assemblies are as follows:

- The ur - It was an assembly of the common people. All people owning land could become its part.

- The sabha - It was an exclusive Brahmin assembly.

- The nagaram - It was an assembly of traders and merchants.

Question B.3:

Bring out the main features of the Chola temples.

ANSWER:

One of the most important aspects of the rule of the Cholas was cultural advancement. Art and architecture reached new heights during their rule. Temples no were ongerthethree-playy prominent emained just the es of worship but rather became the centres of social life. The main hall or the mandapa of the temple often served as the venue for village assembly meetings. Songs and dance wedancesten performed in one temple premises. Bronze statues were also crafted for these temples.

Most of the Chola temples were built in the Dravidian style. Vimana or the tower of the temple decorated by an elaborate gopuram or gateway was an essential feature of Chola temples. Some of the most prominent Chola temples are the Brihadeshwara temple and the Rajarajeshwar temple in Kerala.

Question D.1:

Tripartite struggle

ANSWER:

The constant rivalry between the Palas, the Gurjara-Pratiharas and the Rashtrakutas has been termed the Tripartite Struggle or the struggle between three major powers. One of the major causes of this continuous struggle was the desire to possess the city of Kannauj, which was then a symbol of sovereignty. Another cause was the control of the fertile regions of the Ganges valley. At the end of the long-drawn-out war, the Pratiharas emerged victorious.

Question D.2:

Somnath temple

ANSWER:

The Somnath temple is located in the Kathiawar district of Gujarat and its glory and fame are legendary. The temple is dedicated to Lord Somnath. Mohammad Ghazni attacked this temple during his sixteenth expedition to India. All the gems and other precious possessions of the temple were looted. Mohammad Ghazni carted off the wealth of the temple and destroyed it. Most of the devotees were also killed.

Question D.3:

Al-Beruni's India

ANSWER:

Al-Beruni was a philosopher and a scientist who wrote vividly on Indian sciences, religion and society. His book is a survey of the Indian life based on his experience and observations during AD 1017–1030. He acquainted himself with Sanskrit to understand the Hindu thought of religion. His scientific approach to study religious texts is remarkable. His work Kitab-ul-Hind still serves as important hisan torical source of study of the mediaeval India.

Question D.4:

Palas

ANSWER:

The Palas ruled the medieval east India. According to historical sources, Gopal laid the foundation of this dynasty in AD 750. He was elected by nobles to end the regional anarchy then prevalent. He was an ardent Buddhist and had built a monastery at Odantapuri in Bihar. Another powerful ruler of the Pala kingdom, Devapala came into power in AD 810. It was under his rule that the Palas extended their authority to Assam, parts of Orissa and Nepal.

Question

ANSWER:

The Cholas were one of the most dynamic and powerful kingdoms of the medieval south India. They were not only great administrators but also efficient expansionists. With the sheer strength of their armed or military forces, the Cholas were able to conquer Sri Lanka, Java and Sumatra. Their army consisted of elephants, cavalry and infantry. Also, the strongest men of the kingdom were selected to form the army. Training, discipline and cantonment were given prime attention. The commanders enjoyed the ranks of nayakSenapatiati and mahadandanayaka.

Comments